these details that are fine, where are they? where are the fine details?

If our greatest reserves of meaning-making are expended in moments of outrage and grim appraisal of the planet’s future, just what are the frightened adults supposed to think about in the evening, after the news cycle, when every war front has counted its dead, and the receding day allows lighter fare or even positive erasure?

I can’t see a fucking thing

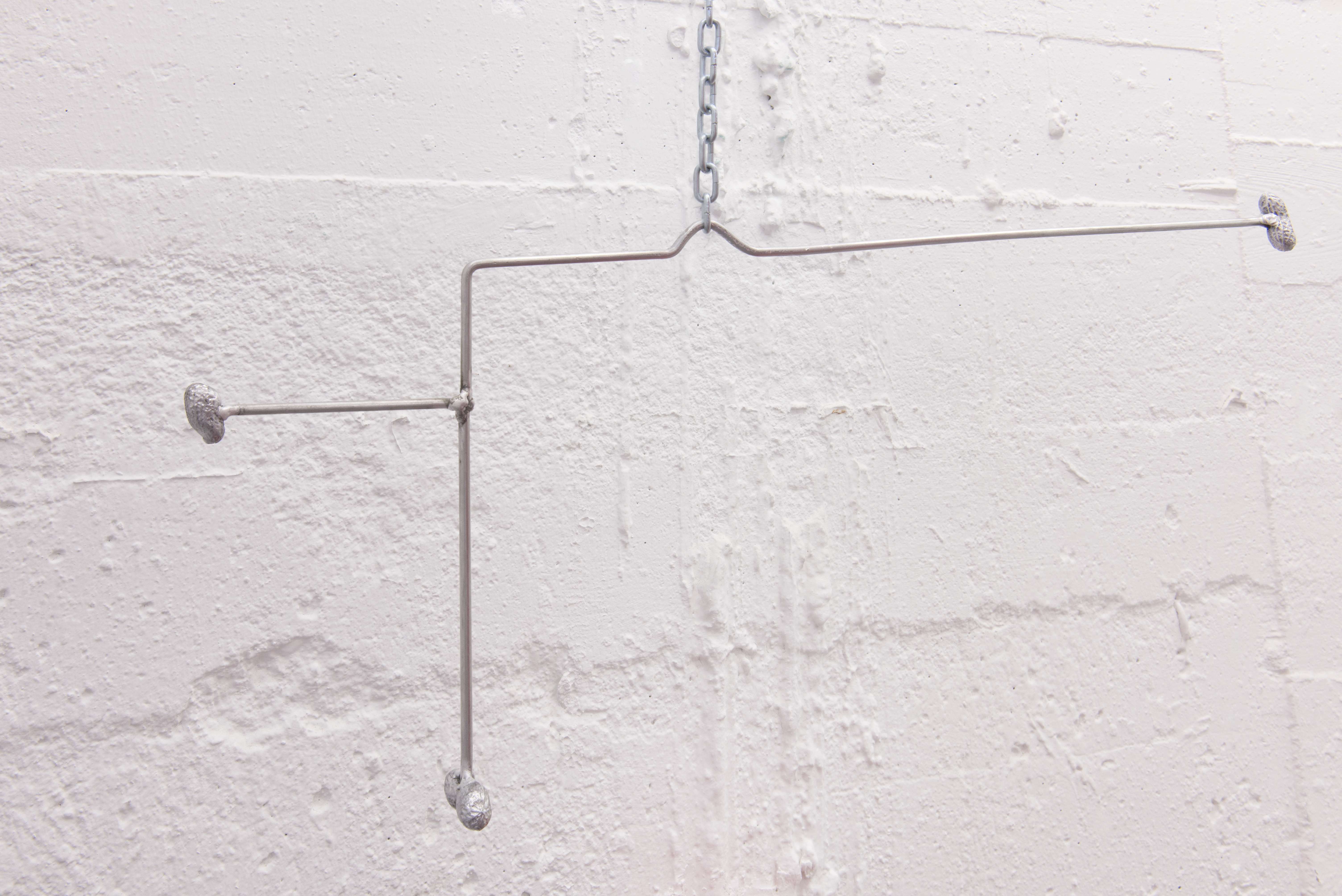

In the annals of vision studies, one of the more startling efforts to corner nature’s bottom line is the method of ‘retinal stabilization’, which, beginning with the 1950s experiments of Riggs and Ratliff, showed that by freezing the motion of a retinal image, the object, or the image of that object, fades from sight. A comparable obsession of eye science has been the study of ‘change blindness’, whereby details that are added to or subtracted from a flashing image go undetected. The eye, in other words, can lose things and miss things. For our purposes, however, what seems most important is how these efforts to isolate the limits of human vision evoke the unseen as a category of event, phenomenon and near-experience that, despite lying definitively beyond our perception, has obsessed us with its demonstration. It is along these lines of inferring what can’t be seen through what can that we may consider a new order of missing details.

…another unveiling of the species…

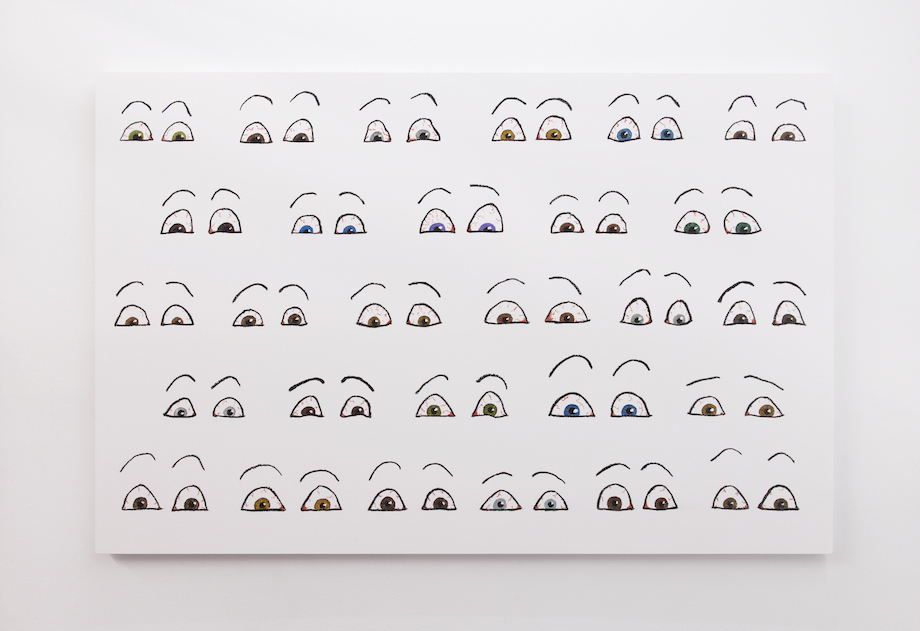

Throughout the series Even Odds, we encounter pairs of images that straddle a count of centuries. Excised from two archival streams—art history and commercial photography —these images show people and styles of peopling that are, let’s just say it, different. They are made of stone, cellophane, light, and represent different human stocks of a given era, real or imagined, a given moment of common knowledge, a probable range of vocabularies or muted adorability, and so also different strategies of looking back, of countenancing the challenge to look, dead ahead or into their business, as profiles involved, as sly head-ons, all of them awake, showing the great exterior of consciousness, across the face and ensured by the eyes.

…but do they like each other?

Perhaps the images don’t suspect their arrangement. After all, who could anticipate that their commitment to an original context, to history itself, would be so overruled? Now, having been roomed together, these faces animate a remarkable tension. It is not the tension of their possible combination, nor even the tension of two people waiting to see who will acknowledge the other first. In fact, they do not appear involved in the suspense that can accompany unintended co-presence in the usual contexts of waiting rooms, elevators, lobbies or buses. Instead, they make us tense by their approximation of an impossible sameness. Because despite their different constitutions, we discern a series of comparable features, alignments of the gaze, or even an expression across time. All of which, as far as our eyes are concerned, checks out okay. And yet, something bends our own heads to the side. It could be that the brain is not a community brain, is not a chorus firing as one. Perhaps some marginal attachments, those neurons who live just outside the visual stream, contest the map-makers’ results. Regardless of how, we feel it, don’t we? That rather than whelming us with this distillation of a human likeness that has prevailed over matter and time, these comparisons of the looking animal are actually a provocation—of more, of see more and do more about seeing more, or give a name to this invisible third agitating in their midst.

the cost of looking

When Lot’s wife was turned to salt for glancing back at a burning Gomorrah, a punishment that is still looking for a crime, never mind one that actually fits, she became an enduring example of the intercepted gaze. To see anyone looking about is to catch them in the act of their most immediate pursuit. Even the pair who don’t know that we’ve caught them looking (the bonneted woman with a gloveless hand to her chin; the man at the piano in earnest transport), who are too zoned out for conscious capture, can be charged with ‘musical enchantment’ and ‘forgetting the day to think instead.’ But after we get over the initial rush of bearing witness, of wading through our own practiced categories and diminutions, these images persist with a kind of second life. Their variations of an improbable likeness begin to inspire a more creative apprehension. Quietly, our viewfinders calibrated to no avail, we become sure that something is happening before our eyes.

- Michael Loncaric, 2017

Paul Kajander's (b. 1980, Vancouver) practice encompasses video, sculpture, installation, photography, sound, performance and drawing. His work has been shown in various exhibition contexts, including the New Media Society; Vancouver, the Hammer Museum; Los Angeles, The SFU Audain Gallery; Vancouver, Daniel Faria Gallery; Toronto, the Seoul Museum of Art; Seoul, The Real DMZ Project; Cheorwon-gun, Art Sonje Center; Seoul and the Western Front; Vancouver. He recently relocated to Guelph, Ontario.