Naive Memory

In my more ingenuous moments, I think of autobiography as a simple process of memory transcription. If a person could just sit still for long enough, it seems, they could drop effortlessly into memory's catacombs. Then, by writing down their findings, the memoirist could let others know who they are, and how they came to be that way.

In my more honest moments, I know this picture is too romantic – puts too much faith in a reader or viewer's empathy. Writing his Interpretation of Dreams in 1899, Sigmund Freud said that it may be possible to reclaim every memory. But for the auto-biographer, these endless recollections can become a deceptive handicap. The writer Janet Malcolm – profiler of psychoanalysts and journalistic biographer nonpareil – described autobiography as a challenge demanding disembarkation from conventional understandings of veracity. "If an autobiography is to be even minimally readable," she wrote after failing to finish her own memoir, the author must subdue “memory's autism, its passion for the tedious." Most importantly, the writer "must not be afraid to invent."

Vanessa Disler's new work suggests an artist navigating this exact challenge of selfstorytelling. Though narratively cryptic, the motifs in her paintings and rebar gates are also charged with corporeal and cultural resonances, that seem almost mythological. One gate entitled Frozen Kiss (Edelweiss Suicide) features an Edelweiss flower, its full white petals translated into quick wire jottings. Hanging by a chain, this flower signifier takes part in a poetic couplet; a symbol of ephemeral nature joined with one of industrial society's domineering power. However this reading is complicated substantially, by a look at the auto-biographical project in which both icons appear.

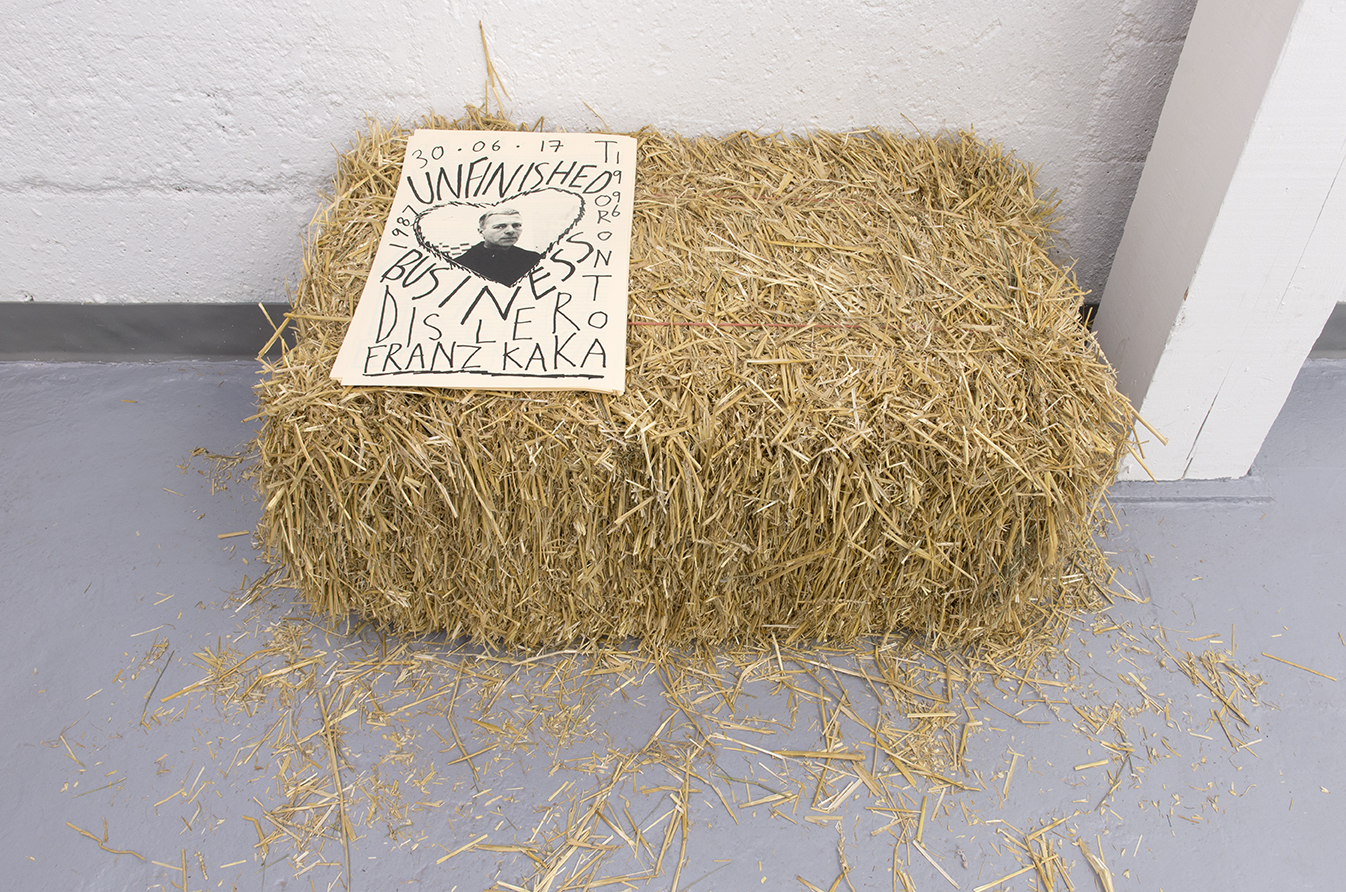

A few days ago, a digital mock-up of the show's poster arrived in my inbox. It shows an image of Vanessa next to her distant relative, the late Swiss painter and writer Martin Disler, overtop the title Unfinished Business. By way of this image, Vanessa's project seems split between a caring impulse to reach into familial and cultural pasts, and a strange Oedipal revenge fantasy. But the title phrase also suggests that the symbols she deals in, may carry persistent and difficult resonances. Looking at that chained Edelweiss, I kept thinking of the ghost of Jacob Marley who, in Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol, torments his former banking partner Ebeneezer Scrooge, from beyond the grave. Oppressed by rattling chains, Marley implores Scrooge to change his avaricious ways. Vanessa's hanging Edelweiss delivers a similar entreaty, foreshadowing the ugly consequences which lurk behind seemingly innocent cultural pride – because of its resilience to Alpine conditions, and supposedly pure whiteness, the flower has become a cypher for Swiss identity.

Of course all people, families, and countries, have bones in their closets. In order to reflect usefully on them, the best strategy might be to draw them out slowly, through poetic allusions. In this way, we can get to know ourselves, without going into self defensive shock. If there is invention at work in Vanessa's memoirist project, it is not a fabrication of facts and anecdotes, but a creative transference of the artist's identity, into icons and phrases. When these icons are modulated by the artist's style and character, their identity takes on that of the human maker. The artworks thus become uncanny, embodied entities.

Importantly, the wider human resonance of this work is enabled by motifs that suggest a human – any human – perceiving itself, vis a vis love, the body, and memory. Flipping through the images that Vanessa sent as she was working on her show, I found another gate Body Work, which contained the words "Liebe" und "Leibe" ("Love" and "Body"). Likewise, in one large painting, the word VERGESSEN (“to forget”) cuts the canvas into quadrants and triangles of bold, brooding color.

What does it mean to caricature memory loss in this way? Mike Kelley's Educational Complex (1995) offers a precedent, if not a conclusive answer. A model produced from memory, of every school Kelley ever attended, the white sculpture resides under a large plexiglass dome, like an institutional wraith. Because absences dominate memory, much of Kelley's model remains empty, indicating that escaped recollection. With the help of a good therapist, Kelley likely could have located these missing details. Instead, he used the absence to bait his audience's projections. As John Miller wrote, despite its seemingly charged personal narrative, Educational Complex was Kelley's “most impersonal work, one that purports to reveal his past, but yields only a blank structure. If these blanks are correlated with trauma of some kind, this entails an imaginative leap. Thus, conjecture becomes key...” Similarly, Vanessa's painting uses an image of forgetting, as a device to enjoin artist and viewer. Given the artistic “father figure” that appears on her exhibition poster, the word VERGESSEN takes on a decidedly feminist bent, satirizing stereotypes of daddy drama – traumas induced by the patriarch.

All the same, a stubborn realism runs through her project. Although both Vanessa and the elder Martin Disler originate in the same Swiss village, she began echoing his symbology in her work, long before discovering him. There is an obvious absurdity – verging on cringeworthy dilettantism – to submitting an artwork to hackneyed psychoanalysis. Still, I've been having trouble resisting the resemblance of this situation, to the recollections described in Freud's dream analyses, whereby deeply buried memories reappear spontaneously in sleep. It seems there is probably a useful explanation to be had, by way of this theory: images implanted in the artist's mind during museum visited, and pictures glimpsed in the early years of life.

Recently, Vanessa told me that she would like haunt the elder Disler in death. Although there was cheek in the remark, there was also conviction. Understanding that haunting is as much a process of incognito observation as tormenting, this desire contains a deceptive political intonation. These days, minds pressured by never-ending and overlapping work schedules, lose their ability to search personal, familial and cultural pasts, much less examine how those things intertwine to form the sum of a person. It seems plausible, then, that Vanessa's recursive and aslant movement through the loving body, the fraught national heritage, and a lost paternal figure, is a protest against forgetting; a poetic resistance to coerced amnesia.

It is true that conservative ideologues have abused cultural memory, converting cheap nostalgia into political capital. In contrast, Disler's gates and paintings weft the matrices of remembering – anxieties felt in the body, symbols recalling images absorbed early in life – into a style of autobiography that is fragmentary by intention.

Her project of re incanting cultural and familial patrimony is something like a caricature of memory recall. But caricature is serious business. It exaggerates our qualities, so we can see them. And maybe so we can get a grip on them, before they sink their wily claws into us.

- Mitch Speed, 2017

Vanessa Disler (b. 1987, Vancouver, Canada) is currently based in Brussels. In 2016 she was a resident at Wiels Centre for Contemporary Art in Brussels. Recent solo and group exhibitions include Damien and the Love Guru, Brussels; CC Stroombeek, Grimbergen; Soloway, Brooklyn; Evelyn Yard Gallery, London; and Juliette Jongma, Amsterdam. Disler is currently working on solo exhibitions that will open this year at Pavilion der Ruhigen, Zurich and at Wiels Project Room, Brussels. From 2013 - 2015 Disler was a resident at De Ateliers, Amsterdam. Since 2010 she has also worked with Nicole Ondre under the alias Feminist Land Art Retreat.