HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander, in it, 2024. Installation views, Franz Kaka, Toronto. Photos by LFdocumentation. |

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander’s Upper Hand

In HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander’s practice, the binary orientation of dichotomy is reprogrammed. In their treatment of reality—meticulous with care and respect, yet laced with noticeable mischief—the boundaries between control and surrender blur. The goal of their operation is not to elevate the low by sneaking it into the circulation of the high. I would call this operation HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander’s “upper hand,” emerging through a labourious engagement with materials—sometimes excessive, embracing the counterproductive. This echoes Georges Bataille’s proposal of “lower than low,” a force that unsettles conventional hierarchies and invites us to reconsider the dormant potential of the physical world, lying just at our feet.1

Site 1

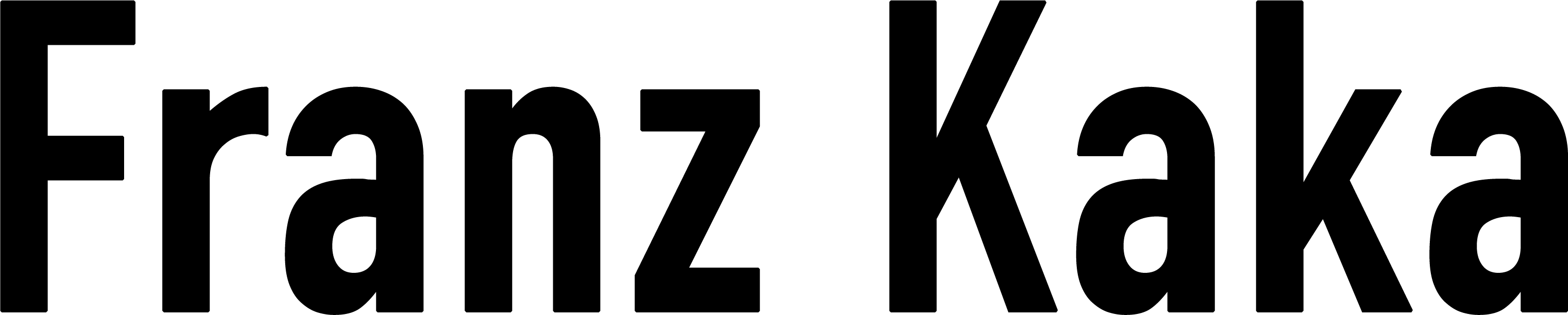

In an alley in Seoul, HaeAhn and Paul—the two forces behind HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander, one with a Korean background and the other Canadian—spotted a filthy, makeshift object. A green metal bin served as a container for cigarette butts, embodying to the artists a certain form of care with its distinct aesthetics, quietly calling for attention.

After passing by it for several weeks, they finally decided to take it. Yet, they didn’t want to disturb the ecosystem of “care and smoking” that populated the alley. The solution was to take the original and replace it with a “bad” reproduction made from an old paint can, spray-painted a similar colour. On the interior of the cigarette bin, what’s lost in speed (2024), they furthered their ongoing exploration with the traditional Korean natural lacquer of Ott-chil (옻칠). Historically, Ott-chil was used for luxury items and ritual objects in Korea, as a symbol of wealth and craftsmanship. In this instance, the material traditionally used for producing a luxurious finish became a bonding adhesive, solidifying a fragmentary pattern of crushed duck eggshells that evoke congealed garbage, cigarette ashes, and butts—a material treatment that precisely captures the essence of the original object: an existence made by waste, for waste.

Site 2

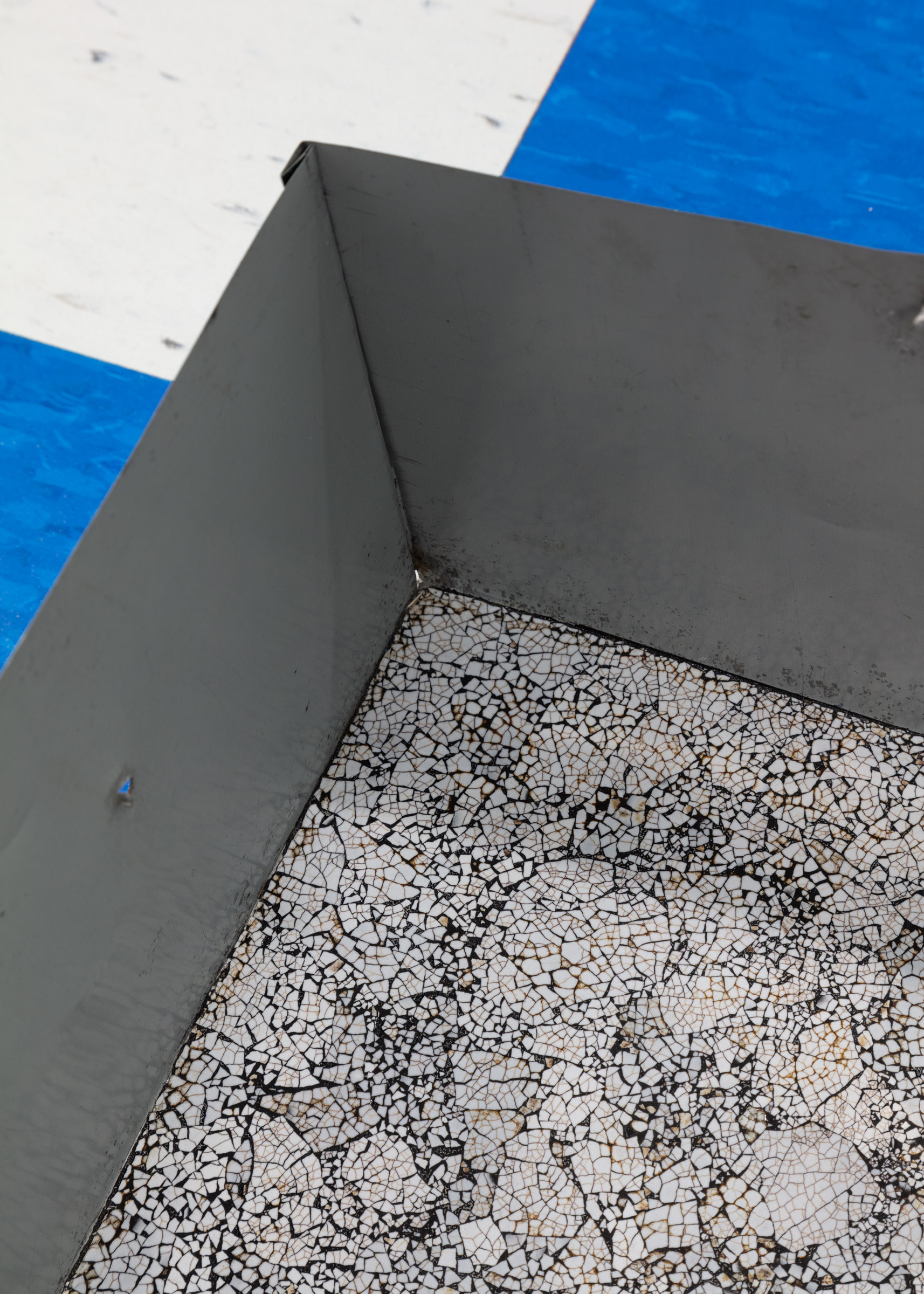

After the Korean War (1950-53), South Korea faced significant challenges in rebuilding its infrastructure and modernizing its urban landscape. Under the leadership of the country’s first president, Syngman Rhee, initial efforts were made to rebuild the country with substantial foreign aid, particularly from the United States. These efforts focused on industrialization and urban development, including the construction of essential infrastructure like sanitation and sewer systems. To critique the process of modernization and the colonial legacy imprinted on the nation, HaeAhn and Paul turned their attention to sewer grates as subtle markers of these rapid transformations.

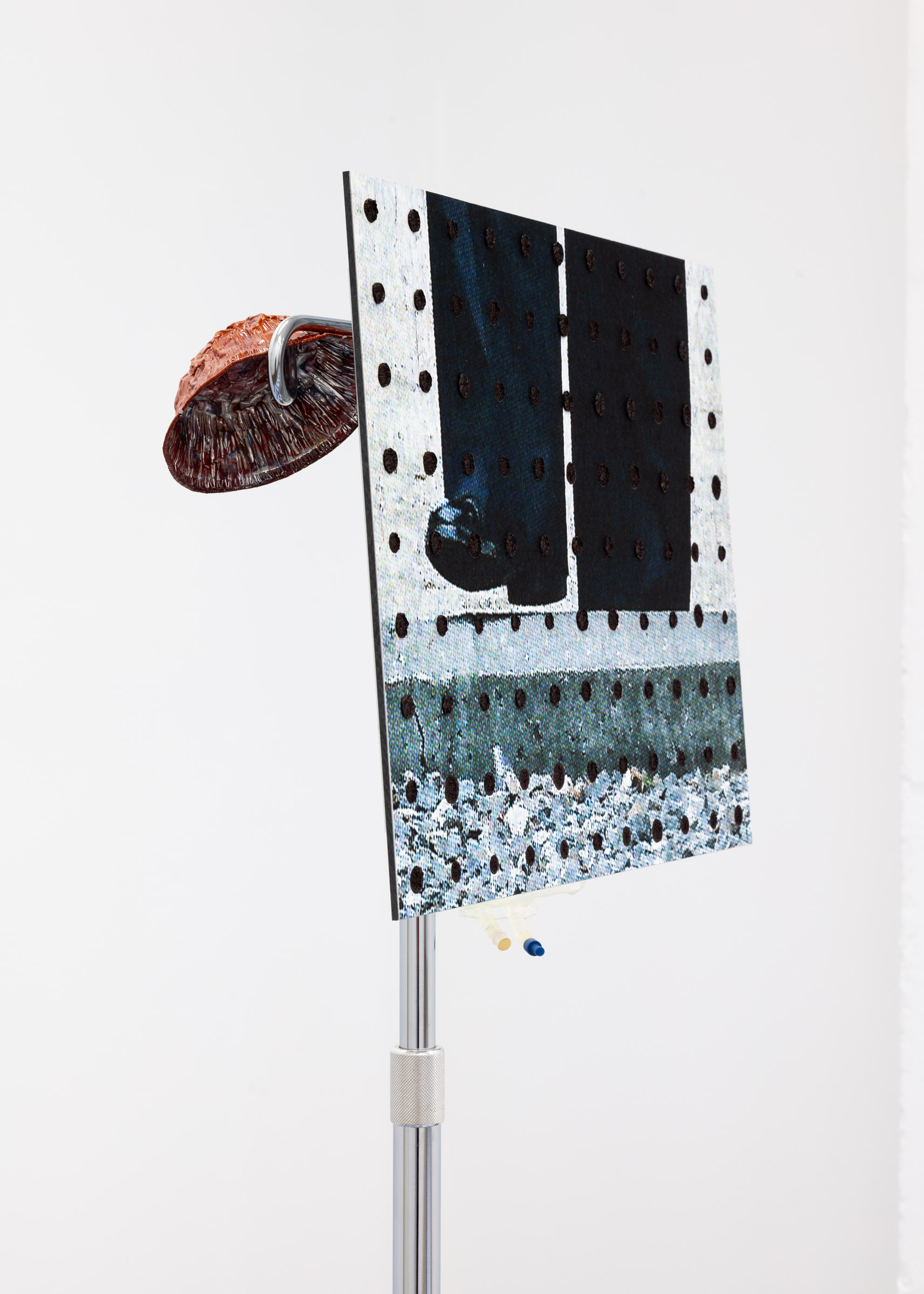

After spending years living under the structures that organize the Western world—a process HaeAhn attributes to assimilation—she was struck by the sense of lawlessness in the social contracts of South Korea. This quality, often found in places undergoing large-scale development, reflects a blend of modernization and postmodernization. Embracing this local trait in their process of making, HaeAhn and Paul would “borrow” sewer grates from the city under the cover of darkness, making pounded aluminum impressions in their studio by hammering late into the night, and then returning them to their original locations. The finished work, Hard Drain (2024) is an aluminum grid—a symbol of modernity—pounded and framed. It is paired with a lacquer piece, Careful Technique of Self-Destruction (2024), representing the catch basin beneath a sewer grate. Applied over many months in numerous layers, the lacquer work serves as an absurd index of labour, with discarded cigarette butts meticulously shaped to scale from mother-of-pearl—a decorative material traditionally used in lacquerware to enhance its value, but here marking the transgression embodied in HaeAhn and Paul’s actions.

Site 3

The DMZ, standing for the Demilitarized Zone, is a buffer zone between North and South Korea. It is four kilometers wide, 200 kilometers long, and heavily guarded. The only part open to the public is the Joint Security Area (JSA), where the armistice agreement was signed to halt hostilities between the two Koreas ending the war. In June 2019, a historic meeting took place there between North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and US President Donald Trump, marking the first time a sitting American president stepped into North Korean territory.

While in South Korea at the time, HaeAhn and Paul gathered newspapers the following day, finding an image of Kim Jong Un stepping from the sandy land of the north, crossing the concrete curb, into the south, finished with drainage stones—a striking juxtaposition of the material realities of the two places. In their reproduction of this found image, HaeAhn and Paul applied a grid of lacquer dots, though “piles” may be a more fitting description of the final presentation. Traditionally, lacquer techniques emphasize a smooth, glossy, and rich finish. Yet here, the lacquer dots are uneven, thick, wrinkled, and irregular, evoking Bataille’s celebration of “scatology,” a gesture sought to subvert societal hierarchies by embracing what is often deemed waste or excess.2 In doing so, much like Bataille’s destabilization of the boundaries between the sacred and profane, HaeAhn and Paul challenge us to confront the visceral and base aspects of reality, a double-layered commentary on the historical moment distilled in the image.

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander’s “upper hand” doesn’t perform the trick of flipping reality; instead, it redirects our gaze to the low, the base aspects of existence, allowing them to remain low, yet charged with agency.

- Georges Bataille. Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927-1939. Edited by Allan Stoekl, University of Minnesota Press, 1985.

- Georges Bataille. Eroticism: Death and Sensuality. Translated by Mary Dalwood, City Lights Books, 1986.

— Yan Wu, 2024

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander would like to thank SuhYeon Park for fabrication assistance and Ian Grieg for salvaged tiles. The artists recognize the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander is the collective practice of HaeAhn Woo Kwon (b. 1985, Daegu, Korea) and Paul Kajander (b. 1980, Vancouver, Canada), working primarily in site-responsive sculptural installation. Through the threading together of given and family names, their practice complicates the notion of individual authorship and addresses the construction of identity. They have exhibited at Franz Kaka (Toronto), Chilgok Transmedia Festival (South Korea), Daniel Faria (Toronto), the Real DMZ Project: Paju (South Korea), Galerie SAW, Korean Cultural Centre (Ottawa), Unit 17 (Vancouver), Galerie Nicolas Robert (Toronto), Trilobite et le Pneu (Montréal), Jack Barrett Gallery (New York), The Small Arms Inspection Building (Mississauga), Julius Caesar (Chicago), and Nerri Baranco (Mexico City).

Yan Wu is a curator, writer, and translator whose work explores the intersection of contemporary art, architecture, and the making of public space. She is currently the Public Art Curator for the City of Markham and a PhD student at the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto. Wu has co-translated seminal books into Chinese, including Rosalind Krauss’s Passages in Modern Sculpture, Lucy Lippard’s Six Years, Dan Graham’s Rock My Religion, and Formless by Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss. Born and raised in Shanghai, she moved to Canada in 2001 and now lives in Toronto.